Sufism plays a key role in interfaith dialogue, fostering mutual understanding through its emphasis on love, tolerance, and spirituality. By addressing moral decline, promoting inner peace, and countering materialism, Sufism contributes to global conversations about spirituality.

Human beings are inherently forgetful, and this fact makes reminding them of essential truths something inevitable. Hence “reminding” is one of the key purposes of prophethood. One such long-forgotten truth they need to be reminded of is the concept of dialogue, a fundamental aspect of human nature and a divine command embedded in the fabric of the universe, known as sunnatullah, or the immutable law of God.

The most profound and comprehensive dialogue occurs between the creator and creation, and one of its manifestations is religious tradition. Thus, even when dialogue becomes strained, it remains an intrinsic element of the human spirit. Hostility and resentment, by contrast, are incidental and temporary. In fact, one could argue that these challenges can act as catalysts for building healthier dialogue and friendships. While dialogue between religious traditions has occurred throughout history, it became a particularly prominent topic in the mid-20th century. Since then, it has evolved into an area of active initiatives, reflecting humanity’s effort to reconnect with a long-lost essence. This growing focus on dialogue appears to arise from recognition of an indispensable need. After this brief introduction, I would now like to turn to my main topic: the role of Sufism in interfaith dialogue.

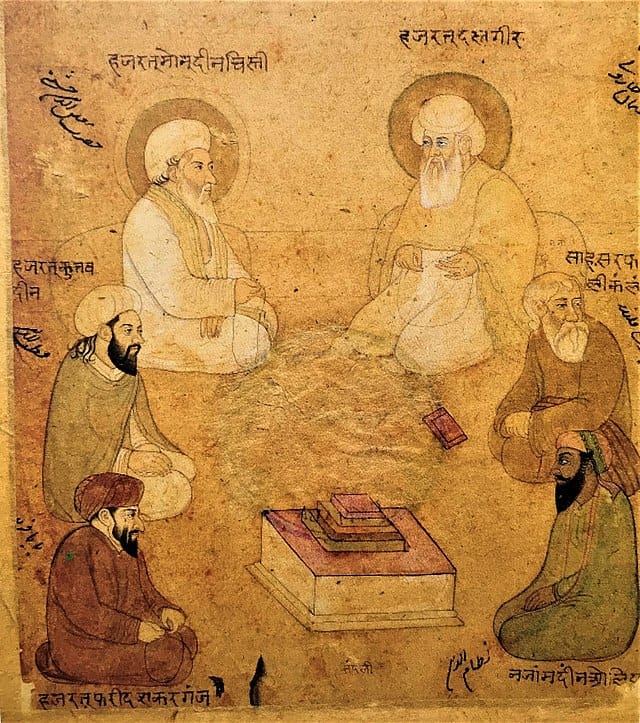

Sufism, representing the inward-focused dimension of Islam, has a longstanding tradition of dialogue with other religious traditions and, indeed, with all of humanity. This process continues to this day, though perhaps not as prominently as before. While certain efforts to establish dialogue are actively pursued in visible and vocal ways, a quieter, more subtle form of interaction has quietly endured for centuries.

Sufi scholars have influenced Western thinkers and societies since the earliest interactions between Muslims and the West. However, this influence has often been overlooked, while the contributions of Islamic culture to the West have chiefly been recognized in scientific fields such as mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and physics. The Islamic world has indeed made significant contributions in these areas, yet the traces of Sufism’s impact on the West have, for some reason, largely been neglected in scholarly examination.

A survey conducted in Europe with 58,135 participants reveals the reasons for embracing Islam among converts. Of those surveyed, 38% cite Mevlana and Imam Ghazali, 32% Risale-i Nur, and 30% Islamic history and Islamic works. According to a different classification, 89% refer to the exemplary life of the Prophet Muhammad as a key reason for their conversion, 28% to the power of Islamic logic in explaining the reason for existence, and 74% to the sense of consolation, peace, and salvation offered by Islam in contrast to materialism. [1]

However, there is a lack of sufficient literature to thoroughly explore the influence of Sufi orders, or ṭarīqas, in this context. A book published in Paris in 1986, From One Faith to Another: Toward Embracing Islam in the West, discusses individuals who converted to Islam through ṭarīqas and Sufism, though the treatment is somewhat superficial. [2] A doctoral dissertation by Ali Köse, “Why They Become Muslims,” based on research conducted in England between 1990 and 1994, remains one of the seminal studies on this subject. [3]

Two factors stand out among the reasons for the growing interest in Sufism and ṭarīqas among Western people:

1- The spiritual crisis and dissatisfaction that Western society is currently experiencing

René Guénon succinctly captures this crisis when he argues that Western society has lost its religious and spiritual foundations, severed its connection with supra-human and divine truths, and become an individualistic, egoistic, purely rationalistic, and materialistic society that values only the individual. [4]

Seyyed Hossein Nasr further elaborates: “The collapse of the value system in the modern world, the growing sense of insecurity about the future, the incomprehensibility of the messages conveyed by religions dominant in the West whose spiritual teachings are gradually fading and, finally, the longing to experience a spiritual dimension in an increasingly deteriorating environment have driven Western people to explore the spiritual values of Eastern religions, and in particular, Sufism.” [5]

2- The attractive features of Sufism

Muhammad Hamidullah observes: “After I began to live in a Western society in Paris, I was surprised and confused to find Christians who had accepted Islam not due to its scholars (ʿulamā’) of jurisprudence or scholastic theology (kalām), but rather Sufis such as Ibn ʿArabī, or Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī. … Now I believe that what will serve Islam today especially in Europe and Africa, is neither the sword nor the intellect, but rather the heart, that is, Sufism.” [6]

Many Westerners have a strong desire to reach the culmination of their spiritual quest, a desire that often leads them to explore esotericism in Eastern religious traditions, particularly Islamic mysticism. Although some elements of Sufism are found in other Eastern spiritual movements, its integration with Islam and the holistic system it offers significantly increases Western interest. Sheikh Nazim Kibrisi describes this development as follows: “Many people I know in the West have read, traveled, listened, and learned. Many of these individuals, who are drawn to the East, going to places like Tibet and India in search of wisdom and enduring countless hardships, risk losing what they find. When they return, they often bring back pearls of wisdom... These pieces, however, are not connected to a common thread. The pearls of wisdom can only be held together through a strong belief and method. You can protect these pearls only if you have a thread.” [7]

What I have briefly presented so far suggests that the element of Sufism should not be overlooked in any dialogue efforts. While its role may not be immediately clear, we can outline the key ways in which Sufism can contribute to the healthy conduct of dialogue:

A- Issues for Social Life

1- Morality: The practical benefit of Sufism lies in its ability to educate individuals and empower them against materialism and the challenges of life. It enables adherents to fulfill religious commandments with ease and pleasure, disciplines them along the way, and fosters good morals and habits. Furthermore, the development of Sufism in the form of ṭarīqas and its integration into society play a significant role in enhancing both individual and social life. It is worth noting that ṭarīqas should consider psychological differences when selecting or guiding their members.

Sufism enriches human life by encouraging individuals to cultivate sincerity, self-accountability, patience, trust in God, self-sacrifice, generosity, and decency in all their actions. It inspires awe in worship, particularly during daily prayers, as well as humility and detachment from worldly concerns (zuhd), prioritization of the hereafter over the worldly life and a yearning for closeness to Allah. Through this depth, individuals refine their character, develop the sense of spiritual tasting (zhawq), show compassion for all beings, and extend support to the weak.

Additionally, Sufism instills a heightened sense of awareness, gentleness (ḥilm), courage, and the ability to love and cherish solely for Allah’s sake. This enduring influence encompasses the subtleties of goodness (birr), benevolence, forgiveness, and the ability to embrace those who turn away from you and to give to those who withhold from you.

In summary, Sufism encompasses nearly all forms of virtuous character. Although moral principles are central to the religious traditions involved in dialogue efforts, both sides of dialogue often lament the moral decline within their societies. I believe that incorporating the essence of Sufi spirituality into these efforts could yield positive outcomes. In an increasingly globalized world, the concept of global morality has gained prominence. It is often argued that moral values are not human constructs but are divine in origin. A fundamental principle of global morality could be expressed as, “You cannot be an ideal person unless you wish for others what you wish for yourself.” This principle lies at the very heart of Sufism.

2- Pressure of physicality: The Western world, as is well known, is grappling with severe crises under the heavy burden of physicality, severed from its spiritual roots. Although not as severe, the Islamic world faces a similar challenge. I believe that one of the most effective ways to provide humanity with a breath of fresh air and restore its original identity is through the Sufi approach and perspective, which harmonizes the physical with the spiritual.

3- Thirst for Love and Tolerance: Our world, shaped by a convergence of numerous factors, is currently experiencing a period marked by serious impudence, insensitivity, lovelessness, hopelessness, suffering, abandonment, aimlessness, worthlessness, and a sense of disconnection from life. Although the intensity of these challenges varies, all of humanity shares in their effects to some extent. Sufism, rooted in love and tolerance and characterized by universal inclusiveness, offers both profound experience and powerful methods for addressing such issues. Other religious traditions are also widely recognized for embodying similar elements. Given that one of the primary goals of dialogue is to provide humanity with a renewed breath of life, I believe that Sufism can play a valuable role in this endeavor. Even though he himself does not fundamentally subscribe to mysticism, Henri Bergson critiques the absence of mystical intuition in modern Western civilization in the “Mechanics and Mystics” chapter of his The Two Sources of Morality and Religion: “Joy indeed would be that simplicity of life diffused throughout the world by an ever-spreading mystic intuition; joy, too, that which would automatically follow a vision of the life beyond attained through the furtherance of scientific experiment.” [8]

B- The Image of Islam in Global Discourse

Islam has increasingly been portrayed as merely a political movement in global discourse. While this perception is partly shaped by the intentions of the producers of the narrative, various movements within Islamic countries also contribute to this portrayal. This is exemplified by the courses on Islam offered in political science departments and similar faculties in the West. However, Islam encompasses rich spirituality, an inner essence, and a soul. Even the social and political institutions of Islam are manifestations of this overlooked spirituality and essence, and they hold meaning only as long as they serve these foundational principles.

Because Muslims adhere to the Quranic command in the verse, “The Hereafter is better for you than the present life” (Q 93:4), they should oppose taking refuge in this life and efforts aimed solely at attaining worldly power. They should reject sacrificing principles for expediency, as well as the legitimization or use of political methods rooted in non-Islamic sources as a means of strengthening Islam. Furthermore, Muslims should view the spread of hatred and enmity as equally harmful as drug addiction, and they should reject such toxic animosity as a valid approach to addressing the intellectual, spiritual, and social challenges facing the Islamic world today.

On the other hand, some have politicized Islam, leading to its perception as a secular, ideological system or an alternative to existing ideologies. This approach not only damages Islam’s integrity but also distances it from its sacred foundation, dragging it into mundane disputes and power struggles. This reductionism enables certain groups to exploit Islam for their personal interests. Once Islam is framed as an ideology, it inevitably becomes associated with acts of brute force and terrorism, which are often seen as tools of ideological systems.

The portrayal of Islam as a mere political movement stems from the reductionist approach of modern thought. One impact of modernity has been to reduce Islam in the minds of many people to a single dimension, such as legalistic regulations, stripping it of the intellectual and spiritual dynamics needed to withstand the assaults of modern ideologies. Among these neglected dynamics is the Sufi tradition, which some have sought to erase from Muslim life.

Globally, a vast majority of Muslims are deeply troubled by this distorted image of Islam. For instance, Dr. Imtiyaz Yusuf, a faculty member at Prince of Songkla University in Thailand, expresses his concerns as follows: “The political Islam that preoccupies the global public portrays Allah merely as a ruler who imposes laws. This raises a question in my mind: Is the God we worship a compassionate Creator, or a political leader, a kingly figure? I often find myself reflecting on this question.” [9] Followers of other religious traditions express similar frustrations. For example, the Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul, Mesrob Mutafyan, advocates for dialogue with Islam and other churches: “The 2000s will be built upon religion. We need to cleanse the word ‘religion’ of an image associated with war, rallies, and endless conflict, and elevate it to a more spiritual and transcendent level.” Many share similar frustrations. [10]

It is also essential to emphasize one fact: political, economic, and even ideological disputes among followers of different religious traditions are often framed and expressed using religious rhetoric, even though religious tradition is not the root cause of global conflicts, and distorted images of religious tradition are projected onto the broader public. Addressing this issue within the framework of dialogue is imperative, and when possible, authorities should issue clarifications to prevent the exploitation of religious tradition. Sufism has historically played a role in maintaining balance, and is thus, I believe, well-positioned to contribute to restoring religious tradition to its rightful spiritual path in an era when efforts to secularize religious tradition are pervasive.

C- Matters of Religious Tradition

First, it must be emphasized that dialogue is not an act of evangelism or proselytization, and it is inevitable for individuals to adhere to the principles of their own faith and defend them if need be. Only then can genuine dialogue occur in the religious matters. Dialogue becomes much easier when the topic at hand is not something people really believe in. In this regard, having an open mind is valuable and is akin to having a room with open windows – provided, of course, that there are walls as well. However, if you have windows in the middle of the desert, it doesn’t matter whether they are open or closed because there are no walls to frame them.

On the other hand, in the evolving dialogue between religious traditions, discussions about the structure of religious tradition currently take a backseat, at least for now. The priority is to understand each other in depth and collaborate to address global challenges. For this reason, I will not dwell extensively on the contributions of Sufism to the dialogue on the structure of religious tradition, but I will highlight some of its key points.

Having noted these two issues, we can now proceed to the relevant topics.

1- Transcendental Unity of Religious Traditions:

The concept of the transcendental unity of religious traditions, which has gained prominence in the West, originates in Sufism. According to Sufism, all religious traditions stem from the same source and share the same purpose; the difference lies in their form and manifestation. The roots of many Sufi elements can be traced back to Abraham, the ancestor of the three scriptural traditions, and his religious tradition, Hanifism.

In Sufism’s understanding of existence, the cosmos is the manifestation of the One in the plural. Religious traditions, in this context, are also manifestations and serve as expressions of the One. Thus, all teachings (provided they are sincere) are reflections of the One, shaped by the requirements of time and space. The formal aspect of religious traditions can be compared to variegated colors: just as every color allows us to perceive the light by dispelling darkness and acknowledging the light, every form, symbol, and religious tradition enables us to follow the ray of revelation, which is nothing other than the ray of truth, back to its Divine source by rejecting falsehood and embracing the truth. [11] This is dictated by God's attribute of justice. If God is just and merciful, He would not deprive any part of humanity of the divine message. This is reflected in the Quran, which declares that a prophet was sent to every nation.

Given this perspective, the reason why prophets, who uphold the universality of truth, are compelled to reject certain traditions is that these traditions have deviated from their original essence, becoming the living dead, devoid of spiritual life, and in some cases, purposeless due to their reliance on dark forces. The elected person who has personally become the living personification of truth cannot simply stand by and watch over these dead forms that are no longer fulfilling their essential roles. [12]

For Islam, this unity is explained as follows: To understand how Islam views itself as the complement and synthesis of the monotheistic religious traditions that preceded it, we must first consider the core elements of Islam: belief (imān), submission of man’s will to God (islām), and spiritual excellence (iḥsān), which are synonymous with faith, law (sharīʿa), and the spiritual path (ṭarīqa), respectively. Belief (or faith) (imān) corresponds to the religious tradition of Abraham; sharīʿa to the religious tradition of Moses; and ṭarīqa to the religious tradition of Jesus. In the religious tradition of the Abraham, the elements of sharīʿa and ṭarīqa are virtually dissolved in imān. In the religious tradition of the Prophet Moses, the element of sharīʿa prevails and dissolves the elements of imān and ṭarīqa. In Christianity, ṭarīqa absorbs and dissolves the other two elements. Submission of human being’s will to God (islām), in the same vein, aims to maintain a perfect balance between these three elements, placing them side by side. This is the foundation of Islamic religious tradition, which explains why it is regarded as a subsumption and synthesis of the previous religious traditions. [13]

Another possible way of reading this view is as follows: The Holy Qur’an says, “And (they) believe in what was revealed to you, and in what was revealed before you.” (Q 2:4) By encouraging the People of the Book to believe, Allah offers them both friendship and convenience and extends them the following invitation: “O People of the Book! There should be no difficulty for you in accepting Islam, nor should it be burdensome for you! He does not command you to abandon your entire religious tradition. However, He says, ‘Practice your beliefs and build them on the religious principles you already possess.’” Since the Qur'an incorporates the virtues of all past scriptures and the basic principles of earlier laws, it is reformatory and supplementary in its approach: it rectifies and improves. It only lays the rules about non-essential matters (furūʿ), which change and evolve with time and space. There is nothing unreasonable about this. Just as there is a need for changes in aspects of life such as clothing, food, and medicine across the seasons, the educational and disciplinary needs also evolve throughout an individual’s life cycle. Likewise, in accordance with common sense (ḥikma) and public interest (maṣlaḥa), subsidiary rulings change according to the stages of human life. One ruling may be beneficial at one time, yet harmful at another. It is for this reason that the Qur'an has abrogated some rulings accordingly. [14]

Some contemporary Christian clergy share a similar perspective, too. Thomas Michael, a participant of an international symposium held in Istanbul in 1998 and a former Secretary-General of the Jesuit Secretariat for Interreligious Dialogue in Rome, explained the above passage in his conference paper: “True Christianity will be freed from superstition and distortion and will unite with Islamic teachings. In fact, Christianity will essentially become a form of Islam.” [15] This perspective can be found in other examples and statements. Therefore, in the dialogue process, it may be valuable to consider this open-minded approach, which was expressed by earlier Sufis and is also shared by traditionalists today.

2- Oneness of God:

Complex concepts like the Trinity and Incarnation in Christianity, along with the varying approaches of other religious traditions to balancing God’s transcendence and immanence, can be more effectively addressed through the explanatory frameworks of the Muḥammadan Reality (al-ḥaqīqa al-muḥammadiyya), the perfect man (al-insān al-kāmil), and unity of being (waḥdat al-wujūd), which are widely discussed in Sufism. These perspectives offer clarity and can help resolve misunderstandings or misconceptions in these areas. Conversely, insights from other traditions can also contribute to a deeper understanding of the Muḥammadan Reality, the Perfect Man, and the Unity of Being. The central aim is to unveil the truth in its most beautiful and pure form. It is noteworthy that Christianity, particularly in its mystical and spiritual dimensions, explores themes that may offer valuable parallels and perspectives on these concepts.

3- Knowledge of God (maʿrifa):

Traditionally, the writers of the Gospels are believed to have received inspiration, not revealion. [16] In Sufism, inspiration is one of the ways to obtain knowledge. Therefore, we believe that mutual dialogue on this point will be beneficial for a better appreciation of both the sacred scriptures and the Sufis’ understanding of knowledge.

4- Several other issues could be the subject of dialogue from a religious perspective due to their affinity with Sufism:

a- The concept of Papal infallibility compared to the notion of (Sufi) sheikhs being safeguarded from significant errors,

b- Supplicating to the Holy Virgin Mary and other figures whose intercession is sought, along with showing reverence for their relics, can be compared to the practice of seeking aid from the spirits of prophets and saints (istighātha) and honoring them,

c- The sinfulness of indulging bodily desires versus the discipline of curbing carnal impulses and lusts,

d- The reliance on religious officials for various religious rituals versus the dependence on a sheikh or caliph for the discipline and practices of the ṭarīqa,

e- The eternal guidance of the Church by the Holy Spirit versus the concept of the Saints of the Unseen (Rijāl al-Ghaib),

f- The formal ceremonies of church officials versus the formal practices of ṭarīqa members.

This list may well include other issues. The Sufi approach, which apparently has Islamic roots with its reliance on revelation, offers enlightening explanations and applications on these issues.

In conclusion, we would like to reaffirm our belief that the Sufi perspective and way of life should not be overlooked if the dialogue between religious traditions is to proceed in a healthy and fruitful manner. This approach will provide us with the opportunity to engage with the spiritual roots of our culture, uncover the noble values it encompasses, and appreciate the values that allowed our ancestors to live harmoniously with a host of nations. Ultimately, this will allow us to reconnect with our own religious tradition and culture, and thus to achieve one of the true purposes of interreligious and intercultural dialogue.

Footnotes

[1] Zaman Newspaper, April 12, 1992.

[2] Lisbeth Rocher and Fatima Cherqaoui, D’une Foi l’Autre, les Conversions à l’Islam en Occident (Paris, 1986).

[3] A. Köse, Neden İslâm’ı Seçiyorlar (Müslüman Olan İngilizler Üzerine Psiko-Sosyolojik Bir İnceleme) (Why They Choose Islam (A Psychosociological Study on the British Who Became Muslims)) (ISAM Publications, Istanbul, 1997).

[4] R. Guenon, La Crise du Monde Moderne (Paris, 1964), 44.

[5] S. H. Nasr, Essai sur le Soufisme, 10.

[6] Mustafa Tahralı, First International Symposium on Islamic Studies, “Batı’daki İhtida Hâdiselerinde Tasavvufun Rolü” [The Role of Sufism in the Conversion Incidents in the West] (Izmir, 1985), 141.

[7] A. Köse, Neden İslâm’ı Seçiyorlar, 128.

[8] H. Bergson, The Two Sources of Morality and Religion, 444.

[9] Excerpt from an interview with Dr. Imtiyaz Yusuf, Aksiyon Magazine (September 26, 1998), 16.

[10] From Mesrob Mutafyan’s interview in Aksiyon Magazine, 22 (31 October-6 November 1998): 204.

[11] F. Schuon, The Transcendent Unity of Religions, trans. Yavuz Keskin (Istanbul, 1992), 14.

[12] Schuon, Transcendent Unity, 21.

[13] F. Schuon, Dimensions of Islam, trans. M. Kanık, 126; S. H. Nasr, Ideals and Realities of Islam, trans. A. Özel, 42.

[14] Said Nursi, Isārātu’l-Iʿcāz, 50.

[15] T. Michel, “Muslim-Christian Dialogue and Cooperation in the Thought of Bediuzzaman Said Nursî,” in “A Contemporary Approach toward Understanding the Qur’an: The Example of Risale-i Nur,” 4th International Symposium, September 20-22 (Istanbul, 1998, unpublished).

[16] “Christians regard all the books of the Bible as part of God’s revelation of himself, but tend to speak of the writers of the books, other than the prophets, not as having “received revelations” but as being “inspired,” that is, as having been guided by God’s spirit, the Holy Spirit. It is generally held that these writers were inspired even when they were incorporating earlier written material; in some cases, of course, this earlier material could also have been produced by the inspired writers themselves. (…) Because the writers had shared in the early experiences of the Church and had important places in it, they might be said to have received a gift of divine wisdom through which their letters came to contain divine truth(s).” (M. Watt, Islam and Christianity Today, 95).

References

Aksiyon Magazine, September 26, 1998; 31 October 31-November 6, 1998.

Bergson, H. The Two Sources of Morality and Religion.

Guenon, R. La Crise du Monde Moderne. Paris, 1964.

Köse, A. Neden İslâm’ı Seçiyorlar (Müslüman Olan İngilizler Üzerine Psiko-Sosyolojik Bir İnceleme) [Why They Choose Islam: A Psychosociological Study on the British Who Became Muslims]. ISAM Publications, Istanbul, 1997.

Michel, T. “Muslim-Christian Dialogue and Cooperation in the Thought of Bediuzzaman Said Nursî,” in A Contemporary Approach toward Understanding the Qur’an: The Example of Risale-i Nur, 4th International Symposium. Istanbul, 1998, unpublished.

Nasr, S. H. Essai sur le Soufisme.

Nasr, S. H. Ideals and Realities of Islam, translated by A. Özel.

Nursi, Said. Isārātu’l-Iʿcāz.

Rocher, Lisbeth and Cherqaoui, Fatima. D’une Foi l’Autre, les Conversions à l’Islam en Occident. Paris, 1986.

Schuon, F. Dimensions of Islam, translated by M. Kanık.

Schuon, F. The Transcendent Unity of Religions, translated by Yavuz Keskin. Istanbul, 1992.

Tahralı, Mustafa. First International Symposium on Islamic Studies, “Batı’daki İhtida Hâdiselerinde Tasavvufun Rolü” [The Role of Sufism in the Conversion Incidents in the West]. Izmir, 1985.

Watt, M. Islam and Christianity Today.

Zaman Newspaper, April 12, 1992.