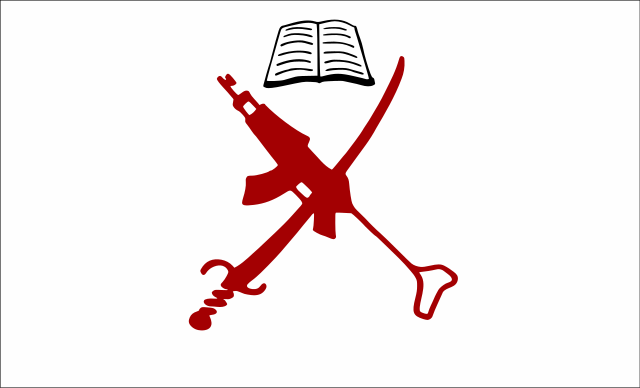

The article probes the link between terrorism and Islam, noting the misuse of concepts like jihād by extremists. It delineates Islamic war ethics, condemns terrorist actions, and emphasizes the distinction between true Islamic teachings and terrorist distortions.

It is a pity that Muslim countries are hurtling through a period of unbridled transformation in which acts of terrorism threaten their internal and external security at an increasingly alarming rate. A host of unfavorable conditions such as economic underdevelopment, social and political disintegration, and cultural corruption foster an environment that breeds terrorist groups in the Islamic world, especially in the Middle East. It is no secret that some terrorist groups are initially supported by the authorities of their country of origin to be used against other terrorist groups, but they grow stronger with state support until they can no longer be controlled. Some terrorist groups, on the other hand, are supported by foreign powers to serve foreign political and economic interests. Sometimes the emergence of some terrorist groups is widely explained by “conspiracy theories.”

For the last few hundred years, the Islamic world lagged in science and technology, and consequently in the economy, which has brought many troubles and vulnerabilities, primarily in the form of cultural crises. In a world divided into blocs, these vulnerabilities have prevented Muslim countries from forming a power center, rendering them vulnerable to external interventions and exploitation. As a result of the cultural crises in this geography, a part of the population perceive their intellectuals and administrators as alienated and react against them. On the other hand, feelings of rebellion swell against the countries perceived as imperialist and the people and groups believed to be in collusion with them. Such a mix breeds terrorism by the nature of things. Even if the people in this geography were not Muslims, the same reactions would occur under the same conditions, and terrorist groups would still emerge. As a matter of fact, ideological polarizations, internal conflicts, reactions against imperialist countries are common in countries that have not completed their development, whether Muslim or not, and this is the situation that is unfolding in Islamic countries. Some individuals and circles associate the emergence of terrorist groups in Islamic countries with Islamic teachings and label terrorist acts as “Islamic terrorism,” while others characterize terrorist acts as “Islamist terrorism” based on the terrorist’s Muslim identity.

I would like to focus on the dimension of associating terrorism with Islam or Muslims and leave other dimensions to the experts. It is clear that the use of some Islamic values, especially jihad, as slogans by terrorist groups and individuals leads to the association between terrorism and Islam. On the other hand, it is natural for terrorists to want to exploit any means, including religious values, to both salve their conscience and gain sympathy from the society. Of course, a terrorist group will use religious values to persuade its militants to engage in terrorist acts. After all, they have no scruples about using any value at hand. This fact aside, can acts of terrorism be methodologically based, as claimed, on the Qur’ān and Sunnah, which are the main sources of Islam? In addition, if the term “Islamist” is used to refer to a person who is adequately knowledgeable about Islamic issues, can such a Muslim to be a terrorist?

The Concept of Jihād

Since some terrorist groups define their actions as jihād, let us first briefly dwell on the concept of jihād. Jihād is any effort, endeavor or attempt made by a Muslim in the way of Allah to win Allah’s favor. In this sense, jihād is a form of worship that will continue uninterrupted until the Day of Judgment. It is any effort, including the one’s effort to discipline one’s soul, to share some important information about the Islamic faith with all people, and to uphold the honor and dignity of Muslims – something for the sake of which the scholars put their knowledge to use, the healthy their services, and the wealthy their riches. Jihād can also be seen as a form of warfare which Muslims are compelled to adopt to eliminate an existing threat when they are attacked or when they receive serious intelligence about an impending attack or to protect their pride and dignity. The number of battles and military operations which the Prophet (peace be upon him!) personally commanded or for which he appointed some of his companions as commanders is more than sixty. In none of these was the Prophet the aggressive party. We can also put this as follows: The Prophet did not attack any polytheistic tribe simply because they were polytheists. All the wars he waged aimed either to repel an ongoing attack or to thwart the preparations of an imminent attack at the outset. In fact, the verses that encouraged Muslims to wage jihād were revealed primarily in relation to wars that had already broken out, as they were no longer avoidable. Therefore, according to the Qur’ān and Sunnah, peace is the essential principle in international relations. War is an exception.

Wars aimed at protecting the existence and dignity of Islam and Muslims make up the short links of the prolonged “chain” of the jihād process. In this sense, i.e., in the form of warfare, jihād is a legitimate institution. It is legitimate for Muslims to react to the occupation of their countries, exploitation, and oppression, as well as to struggle against them; it is their most natural right and duty. However, a crucial point must be considered in this regard: in Islamic Law, just as in all legal systems, not only the goal but also the means pursued to achieve that goal must be legitimate. That is why the Qur’ān does not only encourage believers to engage in warfare but also explains how warfare should be conducted.

Can the killing of civilians, including women, children, and the elderly, be called jihād? Or the indiscriminate firing on school buses with automatic rifles, the burning of houses, shops, and cars, the abduction and even killing of innocents who have no connection to the conflict? How about if these people who are killed and whose property is destroyed are also Muslims? Or, if the groups carrying out these actions do not receive orders from a central authority, are not held accountable to any authority for their actions, and act autonomously, can their actions be considered jihād? Does the action become jihād and the actor mujāhidīn, or jihadist, when the suicide bombers who detonate explosives strapped to their bodies or loaded into their vehicles amid crowds, killing both themselves and innocent people, call their actions jihād and themselves mujāhidīn? Based on the following examples, the readers can decide for themselves whether terrorist acts can be called jihād and those who commit these acts can be called mujāhidīn. Let us clarify the issue with examples of the Prophet’s practices that form the basis of the Islamic Law of War.

Rules of Jihad During Warfare

The rules regarding the warfare dimension of Islamic jihād can be subsumed under the following headings in the light of the Qur’ān and the Sunnah of the Prophet.

1- Not being cruel to the enemy

Under no circumstances did the Prophet aim to crush the enemy physically and spiritually, even in the midst of warfare. We learn from the Prophet that even if they are our enemy, people should be shown mercy when they fall into a pitiful condition. In the 8th year after the Hijra, during the month of Shawwāl, the Prophet sent Khālid ibn al-Walīd with a force of 300 men to confront the Banī Jadhīmah tribe. He instructed him not to fight them unless they initiated it. When the Banī Jadhīmah saw Khālid’s forces, they took up arms. During the battle, a gentle young man was killed by Khālid’s forces in front of the woman he loved. The woman threw herself upon her lover, sighing deeply twice. Her heart could not bear the deep grief, and she died, embracing the man she loved. When this incident was later reported to the Prophet, he became saddened and said, “Was there not one man of mercy among you?” When he was informed that Khālid had killed some of the captives, the Prophet raised his hands to the sky and said, “O God, I declare to You my innocence of what Khālid did. I did not order him to do what he did.”[1]

In another incident, when the conquest of the forts of Khaybar was completed, Ṣafiyya bint Ḥuyayy and her uncle’s daughter were taken captive by Bilāl and walked through some of the Jews who were killed in the battle on their way to the Prophet. When the daughter of Ṣafiyya’s uncle saw her relatives killed, she began to wail and slap her face. The Prophet chided Bilāl, “Has your heart been deprived of mercy? How do you come with two women upon some of their killed men?” Bilāl said, “O Messenger of Allah! I didn’t think you wouldn’t approve of it.” As it is known, the Prophet asked Ṣafiyya bint Ḥuyayy to become a Muslim, and when she did, he married her, so that Ṣafiyya attained the honor of being the mother of the believers.[2]

2- Prohibition of Torture

The Prophet did not permit torture of the enemy. Suhayl ibn Amr was one of the leading polytheists of Mecca. He was one of the tormentors of the Prophet before the Hijra. He was taken prisoner in the Battle of Badr. At one point, he attempted to escape but was captured and brought back. Suhayl was an eloquent speaker who could sway people with his words. ʿUmar said, “O Messenger of Allah! Let me rip out two of his front teeth so that he would never deliver speeches against you again.” The Prophet said, “No, I will not have him tortured. If I did, if I torture him, Allah will punish me. And we should hope that one day he will do something that you will not find disagreeable.”[3] Indeed, after the death of the Prophet, when incidents of apostasy broke out in Mecca, Suhayl ibn Amr said, “O the people of Mecca! You were among the last to enter the religion of Allah. Don’t be among the first to leave it.” He thus persuaded the Meccans not to participate in apostasy.

In another incident, Nabbāsh ibn Qays, a member of the Jewish Banū Qurayẓa tribe who was sentenced to death for his treachery in the Battle of the Trench, was brought before the Prophet. Nabbāsh’s nose had been broken. The Prophet chided the person who brought him in, “Why did you do this to him? Isn’t it enough that he is going to be killed?” The man said: “He pushed me to get away. We got into a scuffle.”

In yet another incident, eight people came to Medina expressing their wish to become Muslims. They were sick and in need of assistance. They got sicker due to the climate of Medina. The Prophet sent them to a pasture where there grazed camels given as alms. They stayed there for about three months until they regained their health. However, they tortured the shepherd looking after the camels to death, cutting off his hands and feet, and pricking his eyes and tongue with thorns. They also stole the camels. When the news reached Medina, a cavalry unit led by Kurz ibn Jābir was hastily dispatched. The cavalry unit captured all the traitors and brought them to Medina. They were charged with robbery, murder, treachery, and apostasy, and punished upon the order of the Prophet.[4] After this incident, the Prophet prohibited torture under any circumstances.[5]

3- Respect for the Dead of the Enemy

The polytheists had the custom of muthla, according to which they cut off the ears, noses and genitalia of the people they killed in war and disemboweled them for the sake of revenge. When the Prophet saw the body of his uncle Hamza mutilated in the Battle of Uḥud, he said in grief, “If Allah grants me victory, I will inflict the same treatment on thirty polytheists in retaliation for what they have done to Hamza.” Upon this, a verse was revealed, “If you retaliate, then let it be equivalent to what you have suffered. But if you patiently endure, it is certainly best for those who are patient” (Q 16:126). The Prophet renounced his oath and paid a certain amount as expiation.[6] Seeing Abū Qatāda rise in a rage at the mutilation of Hamza and prepare to do the same to the dead of the polytheists, the Prophet said, “Sit down! Seek your reward with Allah, o Abū Qatāda! The dead of the Qurayshī polytheists are entrusted to you... Do you want what you have done to be remembered and condemned for a long time along with what they have done?”[7]

As the polytheist army was marching toward Medina for the Battle of Uḥud, it arrived at the village of Abwā,’ where the grave of the Prophet’s Mother, Amīna, was located. Some polytheists proposed to open her grave and take her bones with them, arguing that “If our women fall into the hands of Muḥammad, we will return his mother’s bones to him in exchange for him returning them to us. If not, he will pay us a hefty price for these bones.” Wise ones said, “No, that would not be right. If we do so, the Khuzāʿa and the Bakr tribes will dig up the bones of our dead in return,” and they had the foresight not to set an evil tradition.[8]

4- Not Attacking Civilians and Innocent Targets

Early biographies and histories of military campaigns report numerous incidents in which the Prophet warned his companions about sparing non-combatants even during war.

During the Battle of Ḥunayn, initiated by the tribes of Banī Ḥanīfa and Thaqīf and their allies after the conquest of Mecca, for example, the Prophet saw the body of a slain woman among the dead of the polytheists. He asked, “What is this that I see?” Those who were present said, “This is a woman killed by the forces of Khālid ibn Walīd.” The Prophet then commanded someone present there, “Catch up to Khālid! Tell him that the Messenger of Allah forbids him to kill children, women, and servants!” One of those present said, “O Messenger of Allah! Aren’t they the children of polytheists?” The Prophet replied, “Weren’t the best among you also children of polytheists? Every child is born with a natural disposition and is innocent” (Abū Dāwūd, “Jihād,” 111).

In another incident, the Prophet was seriously ill and was on the verge of his death when news was received that the northern Arab tribes, together with the Greeks, were preparing to attack Medina. The Prophet immediately ordered preparations for a campaign and appointed Usāmah ibn Zayd as its commander. He gave the following instructions to Usāmah: “Fight the attacking disbelievers. Do not violate your covenant. Do not cut down fruit-bearing trees. Do not destroy livestock. Do not kill the clergy secluded in monasteries who are devoted to worship, small children, and women. Do not wish for a confrontation with the enemy. For you may never know; you may be disgraced by them.”[9]

In a similar incident, the Prophet decided to send a unit of 15 men against the Ghaṭafān tribe, which had allied against the Muslims in the Battle of Muta. He instructed Abū Qatāda, who he appointed as the commander of the unit, “Do not kill women and children!” Likewise, upon receiving intelligence that the people of Dūmat al-Jandal were preparing for an attack, the Prophet decided to send a unit of seven hundred men against them. He said to ʿAbd al-Raḥmān ibn ʿAwf, whom he appointed as the commander, “Do not misappropriate the spoils. Do not break your covenant. Do not cut off the limbs of the dead. Do not kill children. This is your covenant with Allah and the exemplary way of His Prophet.”[10]

One of the most striking examples in this regard is the attitude of Khubayb ibn ʿAdiyy in the face of death. Abū Barā, the leader of the Amīr tribe, came to Medina at the beginning of the 4th year of the Hijra. He asked the Prophet to send people to teach Islam to the people of Najd and guaranteed their safety. Upon Abū Barā’s words, the Prophet sent 40 men (or 70 according to other reports) under the command of Mundhir ibn Amr. However, Abū Barā’s nephew Amir ibn Ṭufayl did not honor his uncle’s promise, and with the help of some Banī Sulaym tribes, besieged the delegation at Bi’r al-Maʿūna and slaughtered almost all of them. They took Khubayb ibn ʿAdiyy and Zayd ibn Dathinna to Mecca as captives and sold them to the vicious Quraysh polytheists who were eager to avenge their relatives killed in the battles. Khubayb ibn ʿAdiyy was chained by his feet, waiting for his execution. He asked Mawiya, a former slave woman who was assigned to take care of him, for a razor to clean himself. Mawiya gave a razor to her three-year-old stepson and said, “Go give this to the captive.” Mawiya tells about what happens next: “The child took the razor to the captive. I said, ‘Oh my God, what have I done!’ and ran after the boy. When I arrived, I saw the child sitting on Khubayb’s lap talking to him, and I screamed. Khubayb looked at me. ‘Are you afraid I will kill this child? God forbid, I would never commit such an act. It does not behoove us to take life unjustly. And it’s not you who want to kill me.” Khubayb ibn ʿAdiyy and Zayd ibn Dathinna were taken to Tanim, ten kilometers away from Mecca, where they were speared to death.[11]

All these examples are nothing but the application of a fundamental rule of jihād established by the Qur’ān. This is the rule of fighting only against the combatant. It is the rule of not attacking non-combatant civilians and innocents. Surah al-Baqara stipulates this rule in verse 190: “Fight in the way of Allah only against those who fight you. But do not exceed the limits. Surely Allah does not love transgressors.” The same rule is explained in Surah al-Mā’ida verse 8: “Do not let hatred of a people lead you to transgression and injustice. That is the closer to righteousness.” Treating the enemy without mercy, committing the act of muthla, torturing, killing women and children – these are transgressions and violations which Allah prohibits in the verses.

5- Not Targeting Muslims

It is inconceivable that permission would be granted for the killing of innocent Muslims when it is not granted for innocent non-Muslims even under the conditions of war. Jurists have expressed differing opinions as to whether the Muslims can be fired upon if the enemy uses some Muslims as human shields during the battle and if defeat seems certain when these Muslims are not targeted, provided that they are not directly targeted.

During the lifetime of the Prophet, there was no incident where a Muslim knowingly killed another Muslim in the conditions of war. There was a single incident resulting from a misunderstanding, though. Amr ibn Umayyah, who was in the delegation ambushed in the incident of Bi’r al-Maʿūna and taken captive, was freed for the fulfillment of a vow. On his way back to Medina, he killed two members of the Amr tribe whom he thought were enemies, when in fact they had become Muslims and were carrying a letter of safe conduct given by the Prophet. The Prophet was deeply upset by this mistake and paid the blood money for the two slain men.[12]

After the conquest of Mecca, Ḥārith ibn Dhirār from the Muṣṭaliq tribe came to Medina and became a Muslim. He also helped the whole tribe to become Muslims. The Prophet appointed Walīd ibnʿUqbā to collect alms from the Muṣṭaliq tribe. When they saw Walīd coming as an official of the Messenger of Allah, the Muṣṭaliq tribe went out to welcome him. Seeing them coming towards him, Walīd became frightened and went back to Medina and said, “O Messenger of Allah! The Muṣṭaliq tribe prevented me from collecting alms. They wanted to kill me. They gathered to fight you.” The Prophet sent Khālid ibn Walīd to investigate the situation. It turned out that the situation was not as Walīd ibnʿUqbā had described.[13] Regarding this incident, the following verse was revealed, “O believers, if an evildoer brings you any news, ascertain the truth so you do not harm people unknowingly, becoming regretful for what you have done” (Q 49:6).

God does not approve of Muslims killing Muslims even during warfare, and even unknowingly. In the 6th year of the Hijra, the Prophet arrived at Ḥudaybiya near Mecca with his companions to perform ʿUmra. The polytheists of Mecca did not allow the Prophet and his companions to enter the city. In response, the Prophet signed and sealed a ten-year peace treaty, even though it contained terms unfavorable to Muslims, and chose peace over war. An imminent conflict was thus averted. One of the hidden outcomes of the Treaty of Ḥudaybiya is explained in Surah al-Fatḥ verse 25: “They are the ones who persisted in disbelief and hindered you from the Sacred Mosque and prevented the sacrificial animals from reaching their destination. If it were not for some believing men and believing women there, whom you did not know, you were about to hurt them, and become unknowingly guilty. Thus, God admits into His mercy whomever He wills. Had the unbelievers been clearly distinguishable, We would have inflicted on them a painful punishment.” God did not approve of the unintentional killing by the Muslim soldiers of the Muslims who did not have the opportunity to migrate to Medina and stayed in Mecca. Today, Muslims are deliberately killed in acts alleged to be jihād. How can one conceive that God could be pleased with this?

6- Acting in accordance with the Chain of Command

Another important rule regarding the warfare dimension of jihād is that action must be taken in accordance with a centralized authority recognized by Muslims. Individuals or groups acting independently and without receiving orders from a central authority are unaccountable for their actions and only create chaos. The absence of a central authority does not justify independent irresponsible behavior. Chaos cannot be condoned in the name of jihād. In such cases, corruption of action and deviation from objectives are likely to do more harm than good.

During the era of the Prophet, no incident in which jihād manifested itself as warfare occurred without the command or permission of the Prophet. There were only a few incidents resulting from misunderstanding, and they occurred without the Prophet’s command or permission. These incidents saddened the Prophet, and he admonished the responsible parties. For example, he rebuked ʿAbd Allah ibn Jaḥsh for doing something he was not commanded to, warned Khālid ibn Walīd against killing women and children, and paid the blood money for the Muslims killed by Amr ibn Umayya.

Even the case of Abū Baṣīr is not an exception to this rule. Abū Baṣīr, a member of the Thaqīf tribe, was imprisoned by Meccan polytheists for becoming a Muslim. After the Treaty of Ḥudaybiya, he managed to flee to Medina and took refuge with the Muslims. According to the Treaty of Ḥudaybiya, Muslims would not provide refuge for Muslims who fled from Mecca. When two men came from Mecca to collect Abū Baṣīr, the Prophet complied with the terms of the agreement and handed Abū Baṣīr over. When Abū Baṣīr complained, the Prophet said, “O Abū Baṣīr! Go now. For you and those like you, Allah will create a consolation and expediency.”[14] On the way to Mecca, Abū Baṣīr killed one of the two men who escorted him. The other escaped. Abū Baṣīr went back to Medina and said to the Prophet, “O Messenger of Allah! You kept your word. And God saved me from them.” The Prophet said, “You are a brave man! There is so much you can do if you are surrounded by a group of people. Go now wherever you want.”[15] Abū Baṣīr settled in the coastal town of Is, located on the caravan route between Mecca and Damascus, providing a haven for new Muslims who could not take refuge in Medina. When the group gathering around Abū Baṣīr did not allow the caravans of Mecca to pass, the polytheists of Mecca went to the Prophet and demanded that Abū Baṣīr and his companions be admitted to Medina. The Prophet summoned Abū Baṣīr and his companions to Medina. Abū Baṣīr defended himself as he was supposed to, but he had no intention of acting independently of the Prophet and Muslims. Abū Baṣīr was about to breathe his last when he received the written order of the Prophet summoning him to Medina. After Abū Baṣīr was buried, seventy of his companions returned to Medina and the others to their homelands, according to the written instructions of the Prophet.[16]

7- Humanitarian Aid to the Enemy

Jihād may not always involve causing harm to the enemy. Sometimes, providing humanitarian aid to the enemy in times of dire need also falls within the scope of jihād. Such behavior can also serve to reduce feelings of hostility and weaken the enemy’s resolve. During the years of drought and famine that befell Mecca after the Hijra, the Prophet sent gold to the city so that it can meet its needs for grain, dates, and fodder. Although prominent polytheists of the Quraysh like Umayya ibn Ḥalaf and Ṣafwān ibn Umayya were reluctant to accept this aid, Abu Sufyān expressed his gratitude, saying, “May God reward my nephew with favors, for he has honored kinship.”[17]

Another example of aiding the enemy is the incident of Thumāma ibn Uthāl from the Yamama tribe. After becoming a Muslim, Thumāma went to Mecca to perform ʿUmra. The polytheists understood from the verses and prayers he recited that he was a Muslim. They captured him and tried to kill him. Some prominent polytheists demanded his release, warning that food shipments from Yamama would otherwise stop. When Thumāma returned to his hometown of Yamama, he prevented the shipment of food to Mecca. Placed in dire straits, the Meccans sent a messenger to the Prophet and asked him to instruct Thumāma not to obstruct the food shipments to Mecca. The Prophet sent a written instruction to Thumāma, and the food shipments to Mecca resumed.[18]

8- War as the last resort

The use of force within the scope of jihād is not always the right method. The fact that war was not allowed until the Battle of Badr is a good example of this. In the Second ʿAqaba Pledge, which was made three months before the Hijra, ʿAbbās ibn ʿUbāda said, “O Messenger of Allah! I swear by Allah, who sent you with the true religion and the Book, that tomorrow we will put the people of Mīnā to the sword if you wish.” The Prophet replied, saying, “We are not commanded to do this. Return to your things now.” Does this reply not attest to the fact that not every instance of oppression, insult, and torture, should be responded to by force?

Why did the Prophet rebuke ʿAbd Allah ibn Jaḥsh? In the 17th month after the Hijra, despite that he was sent to the vicinity of Mecca on an intelligence mission, he attacked a caravan belonging to the Quraysh, killing a few people, capturing a few others, and bringing the caravan’s goods to Medina. Did the Prophet do so only because this incident obtained in the month of Rajab, which is one of the sacred months, or also because the conditions were not yet met for an armed struggle with the polytheists of Quraysh and their allies?

The Prophet signed and sealed the Treaty of Ḥudaybiya, which, as stated earlier, contained unacceptable terms, and thus prevented a potentially bloody conflict that could have resulted in unwitting killing of Muslims in Mecca and shedding of much blood. Is the Prophet’s wisdom not aptly illustrated by the Quran 48:25?[19] Was Mecca not conquered without bloodshed after two years of patience? Does this glorious Sunna of the Prophet not prove that it is possible to achieve a goal by means other than the use of weapons in the fight against the enemy?

The Prophet lifted the siege of Ṭā’if, which seemed unlikely to end soon, to prevent the death of the women and children in the fortress due to the blind shots of the catapults and to avoid causing significant loss of life on both sides. Was it not a wise policy and strategy to achieve the goal without war when the people of Ṭā’if, realizing that they were left as a small island in the middle of the Arabian Peninsula, went to Medina and declared their conversion to Islam less than a year later?

In conclusion, can the actions of suicide bombers be justified as jihād when they slaughter civilians, including women, children, and the elderly, in crowded city streets, burn vehicles and buildings, torture and kill innocent people they have taken hostage or kidnapped, detonate explosives strapped to their bodies or loaded into their vehicles among civilians, and do all these without being held accountable? Can they label themselves as mujāhidīn or jihadists? Can these actions be approved by the Qur’ān and Sunnah? What matters is not what we call a thing; what matters is the contents and nature of the thing. It was not Muslims who invented this bloody and dirty method of shedding innocent blood in the struggle to make their voices heard. This method was adopted by extremist Marxist-Leninist terrorist groups, which have the patent for the method. So far, these acts have not helped Muslims in any way. On the contrary, they have marred the image of Islam and Muslims as promoters of knowledge and wisdom, fairness and justice, love and peace. Instead, they have led people to associate Islam and Muslims with terrorism, which is the greatest harm that could be done to Islam. In short, terrorism has no place within the concept of jihād. How Muslims should behave, under what conditions and how and against whom they should fight are all established by the Qur’ān and Sunna. No Muslim can remain a Muslim and diverge from or go against the path set by Allah and His Messenger.

[1]Abū al-Fiḍā' ibn Kathīr, Al-Sīrat al-Nabawiyya (Beirut, 1976), vol. III, 591.

[2]Abū Muḥammad Ibn Hishām, al-Sīraṭ al-Nabawiyya (Beirut, 1971), vol. III, 350-351; Waqīdī Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar, Kitāb al-Maghāzī (Oxford: University of Oxford, 1966), vol. II, 673.

[3] Ibn Hishām, Sirat, vol. II, 304; Ṭabarī, Tafsīr (Egypt, 1954), vol. II, 465, 561.

[4] Abū ʿAbdullah Bukhārī, Al-Jāmīʿ al-Ṣahīh (Istanbul, 1981), “Al-Ḥudūd,” 17-18; Ibn Ḥajjāj Muslim, Ṣaḥīḥ al-Muslim (Istanbul, 1981), “Qusāma,” 9-11.

[5]Waqīdī, Maghāzī, vol. II, 570; Asım M. Köksal, İslam Tarihi (Istanbul, 1981), vol. XIII, 127.

[6] Ibn Hishām, Sirat, vol. III, 101.

[7] Waqīdī, Maghāzī, vol. I, 290.

[8] Waqīdī, Maghāzī, vol. I, 206.

[9] Waqīdī, Maghāzī, vol. III, 117-118.

[10]Ibn Hishām, Sirat, vol. IV, 280-281.

[11]Bukhārī, al-Ṣaḥīḥ, “Maghāzī,” 28; Aḥmad Ibn Ḥajar, Al-Iṣābat fī Tamyīz al-Ṣahāba (Beirut), vol. I, 418.

[12]Ibn Ṣʿad, At-Ṭabaqāt al-Kubrā (Beirut, 1985), vol. II, 53; Waqīdī, Maghāzī, vol.I, 351-352.

[13]Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal, al-Musnad (Beirut, 1985), vol. IV, 279; Muḥammad Zurkānī, Sharḥ al-Mawāhib (Beirut, 1973), vol. III, 47.

[14] Ibn Hishām, Sirat, vol. III, 337.

[15] Waqīdī, Maghāzī, vol. II, 626-627.

[16]Ibn ʿAbd al-Barr, Al-Istīʿāb fī Maʿrifat al-Aṣḥāb, vol. 4, 20; Ḥusayn ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan Diyārbakrī,

Tarīkh al-Khāmis fi Aḥwāl Anfas Nafs (Beirut, 1969), vol. II, 25.

[17]Asım M. Köksal, İslam Tarihi (Istanbul, 1981), vol. XIV, 304.

[18] Ibn Hishām, Sirat, vol. IV, 228.

[19] “They are the ones who persisted in disbelief and hindered you from the Sacred Mosque and prevented the sacrificial animals from reaching their destination. If it were not for some believing men and believing women there, whom you did not know, you were about to hurt them, and become unknowingly guilty. Thus, God admits into His mercy whomever He wills. Had the unbelievers been clearly distinguishable, We would have inflicted on them a painful punishment.”