In the 13th century, Mongol invasions reshaped Eurasia, sparking fears of Gog and Magog. Carpini (1245–1247) and Rubruck (1253–1254) documented Mongol diplomacy and culture, while Ibn Battuta (14th c.) detailed thriving Islamic social and cultural life.

In the thirteenth century, the world witnessed one of the most destructive invasions. Coming from East Asia, Mongols occupied northern China, Central Asia, Persia, and the Caucasus under the leadership of Chingis Khan and of his descendants. Mongols extended their invasion as far as Anatolia and Eastern Europe in the west, and southern China in the east. Suffering exceedingly from the Mongol invasion, Muslims believed that these people coming from the East must have been Ya’jūj Ma’jūj (Gog and Magog) who were supposed to appear at the end of time and destroy most of humanity. Christians were also in shock when Mongols became neighbors to them after wiping out all the big cities of Russia and occupying Bulgaria and Poland. As they saw approaching danger, the hope of Christians that a Christian king from the East would help them to get rid of Islam turned into fear. In such a chaotic atmosphere when the Pope was worrying about the future of Christendom, John of Plano Carpini and William of Rubruck as the representatives of Christians traveled to the territories controlled by the Mongols. Carpini’s travel occurred between 1245 and 1247, and Rubruck’s between 1253-1254. Approximately 80 years later, we see Ibn Battuta, the great Muslim traveler, visiting the area. Besides their historical importance, the travel notes of these three are very exciting even for today’s readers. This essay will briefly analyze their travels in certain respects, aiming to answer the following questions: What were the purposes of their travels? What did they do during their journey? In what ways do their itineraries differ from each other?

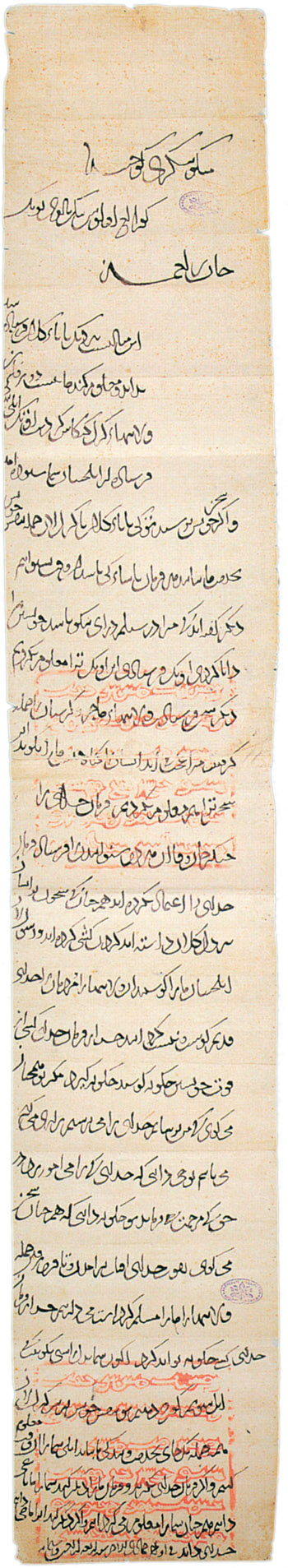

The purpose of Carpini’s journey was more likely diplomatic because the Pope, Innocent IV, appointed him to convey his letter to the Mongol Khan (See the Appendix I and II). However, he had a religious agenda since the Pope was calling the Khan to become a Christian in his letter. Moreover, among his missions was to bring information about all aspects of Mongols to his brothers in faith. He would try to learn “the truth about the desire and intention of the Tartars” and make this known to the Christians; “then if by chance they made a sudden attack they would not find the Christian people unprepared (as happened on another occasion on account of the sins of men) and inflict a great defeat on them.” [1] Carpini and his companion arrived at the Mongol outpost following the northern route through Bohemia,Poland, and Kiev. After an extremely difficult and tiring expedition in the lands of Mongols, they reached their capital,Karakorum, which coincided with the time when Güyük was about to be enthroned as Great Khan. Carpini delivered the Pope’s letter to Güyük, but Güyük’s response to the Pope was disappointing because his denial to become a Christian aside, he was threatening the Pope and the European kings with the threat to wipe them out if they were to disobey his rules. [2] Carrying with him Güyük’s reply to the Pope, Carpini returned back. He submitted what he saw, heard, and learned in Mongolia as a report. In his report, he provides a great deal of details about the geographical features of the Mongol lands, personal characteristics of the Mongols, their religion, customs, and war tactics. He sometimes supports the information he gives with his personal experiences. What we understand from his lively descriptions is that he conducted a very good and accurate observation despite the fact that he had a limited time. A chapter of his report where he deals with how war should be waged against the Mongols is very interesting. Believing that the Mongols were preparing for a war against Christians, Carpini makes a series of recommendation to his people so that they might take measures before their arrival.

Soon after Carpini's return, news that the Great Khan became a Christian began to circulate in Europe. The King of France, Louis IX, who planned a new Crusade against Muslims and intended to get Mongol aid, sent Rubruck to Mongoliawith a letter. After getting prepared in Constantinople, Rubruck embarked upon a sea voyage from Sinop to Crimea. He first arrived at the court of Sartach, a powerful Mongol ruler whose conversion was falsely reported before. Sartach sent Rubruck to his father Baatu, and he sent him to Mangu Khan at Karakorum. After a terrible journey through the endless Central Asia steppes, Rubruck was able to reach Mangu’s court. Staying seven months with Mangu, he returned to Europewith the letter of the Khan. The content of the letter was similar to the one delivered by Carpini before. Namely, the Khan revealed his will to see obedience of the French king in this letter.

Unlike Carpini, Rubruck’s original motive was to be a religious missionary. His purpose was not only to reach Christians living under the rule of the Mongols, but also to preach to all men. Therefore he engaged in religious and theological discussions during his journey, and he had a conversation with the Khan about religion. However, he did not seem successful in his mission since he was able to convert only a few people, and the Khan was not interested in becoming a Christian. As Carpini’s does, Rubruck’s account also provides detailed information about Mongols. He concentrates much more on their dwelling, eating habits, personal appearances, and customs. He reserves long sections for things that would be surprising for a European to see, such as their tent that freely provided them with mobility, and kimiz, a special drink made from a mare’s milk. Moreover, Rubruck mentions the followers of other faiths whom he encountered during his journey such as Muslims, and pagans. Not only does he report other faiths, but also Christians who have different doctrines and practices, such as Nestorians. In addition, his itinerary is richer and more colorful than that of Carpini with respect to personal experiences.

Whereas Carpini and Rubruck traveled to the East for diplomatic and religious purposes, Ibn Battuta’s travel was due to his personal interest. At the beginning, his intention was to perform the pilgrimage, and he left his country,Morocco, after he completed his religious education, and went to Mecca. After the hajj, he decided to see the world. In 1330, he boarded a Genoese merchant ship at the Syrian Port Ladiqiya and reached the south shore of Anatolia. Visiting several Turkish beyliks (amirates) in Anatolia, he went to Crimea through the Black Sea. He stayed with the Mongol Khan of the Golden Horde for a while at Saray and was given the opportunity to accompany his Byzantine wife to Constantinople. When he returned from Constantinople to Saray, he continued his travel through the south and visited famous Islamic centers including Bukhara, Samarqand, and Tirmidh. He finally arrived at the Sultanate of Delhi and he met Muhammad Tughluq, the Sultan of Delhi. Muhammad appointed him as a qādī (judge). After serving the Sultan for seven years, he was sent to the Mongol court of China as the Sultan’s North African qādī ambassador.

Ibn Battuta was welcomed everywhere he visited and treated with respect. He met the most powerful kings, rulers, and sultans of his time: Orhan Bey, the leader of the Ottoman State and the successor of Osman, Abu Said, the last of the Ilkhan rulers, Ozbeg Khan, the Mongol ruler of the Golden Horde, the Emperor of Constantinople, and of course, Muhammad Tughluq, the Sultan of Delhi. He was also introduced to local governors, qādīs, scholars, Sufi masters. Readers find valuable information in Ibn Battuta’s account concerning all aspects of the social life of the places he had visited: Social organizations such as Akhī (fityan) organizations inAnatolia, Sufi khanqahs, cultural activities, sorts of entertainment, religious practices, customs etc. He sometimes mentions non-Muslim minorities living in the Islamic states and the tension between the adherents of different religions. He also makes critical comments on what he observes during his travel. For example, realizing the difference of Orhan Bey from the other amīrs, he seems to draw attention to the promising future of the Ottomans. Another important comment of Ibn Battuta on the Islamization of the Steppe is summarized by Ross E Dunn as follows:

For him conversion was not an important development, rather the establishment of Islam as the “official” religion signified that the Sharia was to have a larger role in society, superseding local or Mongol custom in matters of devotion and personal status. If the Sacred Law were to be applied in the realm, then qādīs and jurists had to be imported from the older centers. [3]

The most important difference between the Catholic and Muslim accounts is that Carpini and Rubruck traveled in alien cultures as strangers while Ibn Battuta was able to find Muslims who would host him everywhere. Therefore, whereas Carpini and Rubruck made observations as outsiders, Ibn Battuta experienced everything as a member of the community. As Dunn points out, “as a jurist, a pilgrim, and a representative of Arab culture” Ibn Battuta “was treated with more honor and deference.” [4] Although the Islamization process of the Steppe was not complete when he was touring the area, Islamic culture came to be dominant, so Ibn Battuta witnessed an amazing social dynamism in the developing cultural and commercial centers. Scholars and merchants were wandering in these centers for any opportunity. As a respected scholar, Ibn Battuta also benefited from this atmosphere and raised his wealth. However, Carpini and Rubruck visited recently destroyed cities and observed lethargy everywhere due to the destructive wars. Although Mongol rulers were trying to improve their territories, allowing commercial activities, even their capital city Karakorum was like a village as compared to the old cities. Carpini and Rubruck encountered many nations and religious groups during their travels but they devoted the largest part of their reports to describe the Mongol rulers. In brief, when examined together, European and Muslim accounts clearly show how the territories under discussion dramatically changed in a short time period.

References

- Dawson, Christopher. Mission to Asia. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1980.

- Dunn, Ross E. The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveler of the 14th Century.Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

- “First Europeans Traveled to Khan's Court,” http://www.silk-road.com/artl/carrub.shtml.

- http://www.asnad.org/en/document/249/

Footnotes

[1] Dawson, Christopher. Mission to Asia. Toronto;Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1980, 3.

[2] See the second illustration and the appendix below.

[3] Dunn, Ross E. The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveler of the 14th Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989, 162.

[4] Dunn, Adventures of Ibn Battuta, 153.

Appendix

Translation of the Arabic letter above (from Dawson, Christopher. Mission to Asia)

Güyük Khan’s Letter To Pope Innocent IV (1246)

We, by the power of the eternal heaven,

Khan of the great Ulus

Our command:

This is a version sent to the great Pope, that he may know and understand in the [Muslim] tongue, what has been written. The petition of the assembly held in the lands of the Emperor [for our support], has been heard from your emissaries.

If he reaches [you] with his own report, Thou, who art the great Pope, together with all the Princes, come in person to serve us. At that time I shall make known all the commands of the Yasa.

You have also said that supplication and prayer have been offered by you, that I might find a good entry into baptism. This prayer of thine I have not understood. Other words which thou hast sent me: “I am surprised that thou hast seized all the lands of the Magyar and the Christians. Tell us what their fault is.” These words of thine I have also not understood. The eternal God has slain and annihilated these lands and peoples, because they have neither adhered to Chingis Khan, nor to the Khagan, both of whom have been sent to make known God’s command, nor to the command of God. Like thy words, they also were impudent, they were proud and they slew our messenger-emissaries. How could anybody seize or kill by his own power contrary to the command of God?

Though thou likewise sayest that I should become a trembling Nestorian Christian, worship God and be an ascetic, how knowest thou whom God absolves, in truth to whom He shows mercy? How dost thou know that such words as thou speakest are with God’s sanction? From the rising of the sun to its setting, all the lands have been made subject to me. Who could do this contrary to the command of God?

Now you should say with a sincere heart: “I will submit and serve you.” Thou thyself, at the head of all the Princes, come at to serve and wait upon us! At that time I shall recognize your submission.

If you do not observe God’s command, and if you ignore my command, I shall know you as my enemy. Likewise I shall make you understand. If you do otherwise, God knows what I know.

At the end of Jumada the second in the year 644.

The Seal

We, by the power of the eternal Tengri, universal Khan of the great Mongol Ulus – our command. I this reaches people who have made their submission, let them respect and stand in awe of it.